In a rapidly urbanizing world, the decision to build new versus repurpose old structures presents a critical choice for developers, investors, and city planners. Adaptive Reuse (AR), the process of converting an existing structure into a new use, has emerged not just as a sustainable trend but as a highly strategic financial and architectural methodology. Moving beyond simple cosmetic updates, AR involves fundamentally changing a building’s function—turning an old factory into loft apartments, a school into a community center, or a church into a restaurant.

This approach is particularly compelling in mature urban areas where land scarcity is acute and heritage preservation is vital. Crucially, from a financial perspective, Adaptive Reuse frequently offers a pathway to significantly lower overall renovation costs and expedited project timelines compared to new construction. This detailed exploration delves into the financial mechanics, structural advantages, environmental impact, and complex challenges associated with leveraging existing building stock for a new, profitable life.

I. Financial Framework: Deconstructing the Cost Advantages

The primary driver for the adoption of Adaptive Reuse is often the compelling financial calculus. While new construction involves foundational costs, site preparation, and extensive structural development, AR strategically minimizes these expenses.

A. Eliminating Major Site and Foundation Expenses

The most immediate and significant cost saving in Adaptive Reuse comes from the presence of an existing structure.

- A. Foundation and Substructure Preservation: The costly and time-consuming process of excavation, soil stabilization, and laying new foundations is largely avoided, as the existing building already possesses a functional foundation capable of supporting the structure.

- B. Site Preparation Savings: Demolition and site clearing costs, which can be substantial and generate significant waste removal fees in new construction, are drastically reduced or eliminated entirely.

- C. Utilities Infrastructure Retention: Existing connections to essential municipal services (water, sewer, electric, gas) are often salvageable, avoiding high connection and tie-in fees associated with brand-new developments.

B. Leveraging Existing Structural Shell

The building envelope—the walls, floors, and roof—represents a major expense in conventional construction. AR capitalizes on this existing asset.

- D. Wall and Facade Retention: Retaining the primary structural walls and the exterior facade saves on the cost of purchasing, transporting, and erecting new materials like concrete, steel, or masonry.

- E. Reduced Material Procurement: The volume of new materials required is confined mainly to interiors, mechanical systems, and minor structural modifications, streamlining the supply chain and lowering material purchasing volume.

- F. Tax Incentives and Financial Credits: Many jurisdictions offer substantial federal, state, or local tax credits, grants, or expedited permitting for projects that involve the preservation or adaptive reuse of historic or older buildings, directly lowering the project’s net cost.

C. Accelerated Project Timeline and Carrying Costs

Time is money in development. Adaptive Reuse projects often feature significantly shorter overall timelines than ground-up construction, which directly impacts project financing.

- G. Reduced Interest and Holding Costs: Shorter construction periods translate into fewer months of paying interest on construction loans and lower developer holding costs for the property.

- H. Faster Revenue Generation: Projects can reach the occupancy or operational stage sooner, allowing investors and owners to begin generating rental income or business revenue much earlier.

II. Structural and Design Opportunities

Beyond cost, older structures often possess intrinsic qualities—structural robustness and unique architectural characteristics—that are expensive or difficult to replicate today.

A. Inherited Structural Resilience

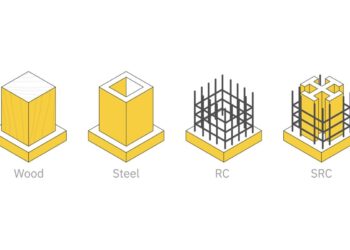

Buildings constructed in the mid-20th century or earlier frequently feature over-engineered structures built with robust, high-quality materials, such as thick-walled masonry, heavy timber, or substantial concrete.

- I. Higher Load-Bearing Capacity: Older industrial or commercial buildings often have floors and beams designed to support heavy machinery, giving the building a superior load-bearing capacity that can easily accommodate modern office or residential layouts.

- J. Durability and Longevity: The quality of original materials, particularly antique brickwork and old-growth timber, can offer durability that surpasses contemporary, mass-produced alternatives.

B. Architectural Character and Market Appeal

AR inherently creates spaces with unique aesthetic appeal, which translates into higher market value and tenant desirability.

- K. Unique Design Elements: High ceilings, exposed original materials (beams, brick), large window openings, and distinctive facades provide character that commands higher rents or sale prices than generic new builds.

- L. Creating Niche Market Value: The unique industrial aesthetic of former warehouses, for example, is highly sought after by creative firms and young professionals, allowing developers to target lucrative, niche markets.

III. Addressing the Environmental and Societal Imperatives

In an era of increasing environmental accountability, the sustainability credentials of Adaptive Reuse provide a significant advantage in branding and compliance.

A. Minimizing Construction and Demolition (C&D) Waste

C&D waste is a major component of landfill material globally. Adaptive Reuse is fundamentally a waste-reduction strategy.

- M. Reduced Landfill Contributions: By retaining the majority of the structure, the project avoids sending tons of concrete, wood, steel, and other debris to landfills, adhering to modern environmental mandates.

- N. Material Recycling Efficiencies: While some internal elements might be replaced, the high cost of recycling major structural materials like concrete and steel is avoided entirely.

B. Lowering Embodied Energy

Every building material produced has embodied energy—the sum of energy required to extract, manufacture, transport, and install it.

- O. Preserving Embodied Energy: AR preserves the massive amounts of energy already “invested” in the existing structure, avoiding the need to expend new energy to create replacement materials, leading to a much lower overall carbon footprint.

- P. Improved Sustainability Metrics: Projects that incorporate AR often score highly on sustainability rating systems (e.g., LEED, BREEAM), enhancing their appeal to environmentally conscious tenants and investors.

C. Community and Cultural Preservation

Adaptive Reuse is a vital tool for maintaining the cultural identity and urban fabric of a neighborhood.

- Q. Heritage Retention: It ensures that architecturally significant or culturally important landmarks are preserved and remain integrated into the community, preventing the loss of local history.

- R. Neighborhood Stability: Reusing existing, often centrally located buildings maintains the established density and walkability of a neighborhood, supporting local businesses and existing infrastructure.

IV. The Complexities and Hidden Costs in Adaptive Reuse

While the advantages are numerous, AR is not without its specific set of risks and challenges that must be meticulously managed to prevent budget overruns. These complexities primarily concern hidden conditions and regulatory compliance.

A. Unforeseen Structural and Environmental Issues

The most significant financial risk in AR is the potential discovery of hidden problems once demolition begins.

- S. Hazardous Materials Abatement: Older buildings often contain costly and regulated hazardous materials, such as asbestos, lead-based paint, and Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs), requiring specialized (and expensive) remediation and disposal before work can proceed.

- T. Undisclosed Structural Deterioration: Problems like water damage, hidden foundation cracks, pest infestation (termites, rot), or corrosion in steel elements may require extensive, unbudgeted repairs.

- U. Seismic and Building Code Upgrades: Often, the structure must be upgraded to meet modern seismic, wind-load, and fire codes, which may require significant structural reinforcement (e.g., adding shear walls or strengthening columns).

B. Navigating Code Compliance and Permitting

Fitting a new use into an old structure requires a sophisticated understanding of current building codes and regulatory bodies.

- V. Accessibility (ADA) Compliance: Existing structures frequently lack modern accessibility features, requiring costly installations of elevators, ramps, and accessible washrooms.

- W. Fire and Life Safety Systems: Older buildings typically need complete overhauls of fire suppression (sprinklers) and alarm systems to meet current safety standards for the new occupancy type, a considerable expense.

- X. Zoning and Use Permits: Obtaining the necessary variances or conditional use permits to legally transition from the old function (e.g., industrial) to the new one (e.g., residential) can be a lengthy, complex, and costly process.

C. Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing (MEP) Overhauls

While the shell is saved, the internal systems of an older building are almost always obsolete and require replacement.

- Y. Inefficient HVAC Systems: Existing heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems are usually energy inefficient and insufficient for the new occupancy density, necessitating complete replacement.

- Z. Electrical Load Requirements: Modern office or residential uses demand significantly higher electrical loads than historic uses, requiring new service entrances, wiring, and distribution panels throughout the building.

V. Best Practices for Successful Adaptive Reuse Projects

Mitigating the risks associated with AR requires a disciplined and highly specialized approach during the planning and execution phases.

A. Comprehensive Due Diligence and Pre-Assessment

Thorough investigation of the existing conditions is the single most important factor in cost control.

- AA. Invasive Testing: Utilize invasive inspection techniques, including selective demolition, core drilling, and environmental sampling, early in the project to accurately quantify the scope of required abatement and structural reinforcement.

- BB. Detailed Historical Documentation Review: Researching the building’s original plans, construction methods, and previous renovation records provides invaluable clues about hidden conditions and structural makeup.

B. Integrated Design and Engineering Team

AR requires close collaboration between architects, structural engineers, and MEP specialists who possess expertise in dealing with existing buildings.

- CC. Phased Engineering Strategy: Adopt a phased engineering approach where structural solutions are designed in tandem with MEP integration, ensuring new systems can be routed effectively within the constraints of the existing structure.

- DD. Value Engineering for Retention: Focus value engineering efforts not on cutting costs, but on identifying the maximum amount of original material and structure that can be preserved and safely incorporated into the new design.

C. Budgeting and Contingency Planning

Due to the high potential for unforeseen conditions, AR projects require a substantially larger contingency budget than new construction.

- EE. Higher Contingency Allocation: A recommended contingency fund of 15% to 25% of the construction cost, rather than the standard 5% to 10% for new builds, should be allocated to absorb unforeseen remediation or structural costs.

- FF. Early Procurement of Long-Lead Items: Order specialized or custom-fit items early, anticipating that non-standard dimensions in the old structure may complicate the installation of new windows, doors, or custom mechanical components.

Conclusion: Adaptive Reuse as a Financial and Sustainable Necessity

Adaptive Reuse is far more than a niche market activity; it represents the financially prudent and environmentally responsible future of urban development. By strategically capitalizing on the immense, often over-engineered structural capital embodied in older buildings, developers can bypass major construction expenses, accelerate timelines, and unlock unique architectural value. While the process demands specialized expertise and a robust contingency plan to manage the unique risks of pre-existing conditions, the reward—lower renovation costs, higher market differentiation, and compelling sustainability metrics—positions Adaptive Reuse as the optimal strategy for revitalizing the built environment and appealing directly to a new generation of conscious consumers and investors.