Adaptive Reuse: Lower Renovation Costs

Adaptive reuse, often called repurposing, is a powerful and increasingly popular strategy in real estate development and urban planning. It involves converting an existing building—perhaps a forgotten factory, an old school, or a disused warehouse—into a new, functional space, typically for a different purpose than its original design. For developers, investors, and community planners, this approach is not merely an architectural trend; it’s a profound economic model that directly tackles two of the most significant challenges in construction: high renovation costs and extended project timelines.

The core premise of adaptive reuse is simple yet transformative: Why demolish and rebuild when you can restore and repurpose? This question is the linchpin of a strategy that can dramatically reduce overall development expenses, expedite the permitting process, and inherently contribute to sustainability goals. While conventional new construction requires massive capital outlay for foundation work, structural framing, and external envelopes from scratch, adaptive reuse leverages the existing built environment, turning potential liabilities into valuable assets.

This detailed guide will explore the financial mechanics, practical advantages, and strategic execution of adaptive reuse, demonstrating how it consistently offers a path to lower renovation costs and a higher return on investment (ROI) compared to traditional demolition and rebuild projects.

Financial Pillars of Cost Reduction in Adaptive Reuse

The savings inherent in adaptive reuse are multifaceted and extend beyond the superficial. By meticulously analyzing the project lifecycle, it becomes evident where the most substantial financial benefits accrue, appealing directly to insurance and construction stakeholders interested in managing risk and optimizing expenditure.

A. Minimizing Demolition and Debris Removal Expenses

The immediate and most tangible savings come from avoiding total demolition. New construction necessitates the complete destruction of the existing structure, a process that is both costly and time-consuming.

Costly Labor and Equipment: Demolition requires heavy machinery, specialized labor, and extensive on-site safety protocols, all of which drive up initial expenses.

Waste Disposal Fees: A significant portion of the cost involves disposing of massive volumes of construction and demolition (C&D) waste, which often carries substantial tipping fees at landfills. The sheer scale of debris from a commercial building teardown can translate into hundreds of thousands of dollars in disposal costs alone.

Reduced Insurance Risk: Less on-site, large-scale, explosive activity translates to a lower risk profile during the initial project phase, which can favorably impact builder’s risk insurance premiums.

By choosing adaptive reuse, developers skip these massive demolition outlays, focusing instead on selective, surgical deconstruction or minor interior strip-outs, a far more economical process.

B. Leveraging Existing Structural and Foundational Integrity

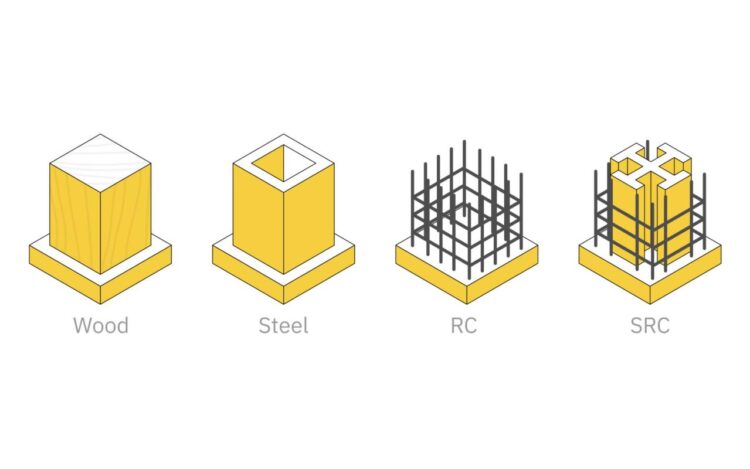

The most expensive components of any building project are typically the foundation and the primary structural shell (walls, columns, beams). Adaptive reuse inherently capitalizes on these existing assets.

Foundation Savings: Developers avoid the extensive geotechnical surveys, deep excavation, and concrete pouring required for a new foundation. As long as the existing foundation is sound and can bear the new loads, the savings are substantial.

Shell Enclosure: The exterior walls and roofing, often referred to as the building’s envelope, are retained. Constructing a weather-tight shell from scratch accounts for a massive percentage of a new building’s budget. Retaining it drastically reduces material costs for siding, masonry, and temporary weather-proofing during construction.

Accelerated Schedule: Because the structure is already standing, the most time-consuming phase of a new build—getting the building “out of the ground” and “dried in”—is eliminated or severely shortened, contributing to lower soft costs like financing interest, site management, and project overhead.

C. Accessing Historic and Sustainable Tax Credits

Adaptive reuse projects frequently qualify for significant financial incentives that are unavailable to new construction. These credits directly offset capital expenditure, acting as a crucial cost-reducing mechanism.

Historic Preservation Tax Credits: In many jurisdictions, converting historically significant structures—such as old mills or rail depots—into residential or commercial spaces allows developers to access federal and state tax credits. These can sometimes cover a significant fraction (e.g., 20% to 40%) of the total qualified rehabilitation expenses.

Sustainability and LEED Credits: Because adaptive reuse is an intrinsically sustainable practice (it reduces embodied energy and landfill waste), projects often find it easier and less expensive to achieve green building certifications like LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design). These certifications can unlock further local rebates, faster permitting, and improved market value.

- Strategic Advantages Beyond Direct Construction Costs

While direct savings on materials and labor are important, the long-term, strategic advantages of adaptive reuse further solidify its cost-efficiency. These benefits address the broader financial and logistical risks of development.

A. Expedited Permitting and Regulatory Compliance

New construction projects often face complex and protracted approval processes, particularly in densely populated urban areas, due to requirements for environmental impact statements, zone changes, and neighborhood protests.

Fewer Zoning Hurdles: Converting a building often falls under less restrictive permit categories than starting anew, especially if the new use is compatible with the existing zoning or if the developer seeks a relatively straightforward conditional use permit.

Reduced Public Opposition: Adaptive reuse is generally viewed favorably by local communities and planning boards as it preserves local heritage and avoids the disruption of large-scale, long-term construction associated with demolishing and rebuilding. This goodwill often translates into a smoother, faster approval process, preventing costly project delays.

B. Faster Time-to-Market and Revenue Generation

In development, time is money. Every month a project is delayed means another month of interest payments on construction loans, administrative costs, and, critically, lost rental or sales revenue.

Shorter Construction Cycle: With the shell already in place, the construction phase focuses primarily on interior fit-out, MEP (Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing) upgrades, and façade refurbishment. This typically takes significantly less time than full new construction.

Quicker Lease-Up: Repurposed buildings, particularly those that retain historic character (e.g., exposed brick, large windows, high ceilings), often possess unique architectural features highly valued by tenants, especially in the office and loft apartment markets. This architectural uniqueness can lead to quicker lease-up periods and potentially higher rents, accelerating the developer’s ROI.

C. Mitigating Supply Chain and Material Cost Fluctuation Risks

Traditional construction is extremely vulnerable to global supply chain issues and volatile commodity prices (e.g., steel, lumber, copper). A project that relies less on massive quantities of newly sourced raw materials is naturally more resilient to these market risks.

Reduced Material Dependency: By reusing the existing structure, the project’s dependency on large, high-cost, and volatile commodities is dramatically lowered.

Predictability in Budgeting: The majority of the cost shifts to interior components, finishes, and MEP systems, which are generally easier to source domestically and have more predictable pricing than structural elements, allowing for tighter budget control and reducing the risk exposure for project insurance underwriters.

Key Technical and Practical Considerations for Adaptive Reuse

While the financial benefits are clear, successful adaptive reuse demands specialized expertise in assessment, engineering, and construction management. Neglecting these areas can quickly erode potential cost savings.

A. Initial Due Diligence: Comprehensive Building Assessment

Before any hammer is swung, an exhaustive assessment of the existing structure is paramount to accurately budget the renovation. A detailed Property Condition Assessment (PCA) is crucial.

Structural Integrity Analysis: Engineers must evaluate the condition of load-bearing elements, looking for rust, cracks, shifting, or material fatigue. They must also confirm if the existing structure can support the proposed new use’s live and dead loads (e.g., converting an office building to heavy-load residential apartments).

Hazardous Material Survey: Older buildings almost certainly contain materials like asbestos, lead-based paint, and potentially polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). The cost of abatement must be thoroughly calculated and factored into the budget. Failing to account for this can lead to massive cost overruns and legal issues.

MEP Systems Evaluation: The age and condition of existing mechanical (HVAC), electrical, and plumbing systems determine if they can be integrated into the new design or must be fully replaced. While often requiring replacement, any usable components can translate to immediate savings.

B. Navigating Building Code Compliance and Accessibility

One of the biggest non-cost related challenges is ensuring the old structure meets modern building codes and accessibility standards, particularly the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Life Safety Upgrades: Older buildings frequently require major upgrades to fire suppression (sprinklers), fire alarm systems, and exit pathways to meet current life safety codes. These are non-negotiable and often represent a significant portion of the renovation budget.

Seismic and Wind Load Upgrades: In areas prone to seismic activity or high winds, the existing structure may need extensive retrofitting—known as seismic strengthening—to comply with modern engineering standards. This specialized work can be expensive but is essential for asset longevity and to secure favorable property insurance rates.

C. Design Efficiency: The “Fitting” vs. “Forcing” Principle

The most cost-effective adaptive reuse projects are those where the new use “fits” the existing structure’s rhythm and form, rather than “forcing” a new design onto an incompatible shell.

Optimizing the Existing Grid: A clever designer will utilize the existing column grid and floor plate dimensions to lay out the new spaces (apartments, offices, retail units). Trying to dramatically change the structural layout by moving stairwells or punching large new holes in slabs quickly increases structural modification costs.

Creative Material Sourcing: Reusing or salvaging materials from the selective deconstruction (e.g., repurposing old wood flooring, salvaging unique doors, or using original brickwork) not only saves money but also adds character that increases the market appeal of the finished product.

Case Study Examples: Proving the Economic Viability

The viability of adaptive reuse is demonstrated by countless successful projects globally, ranging from small-scale residential conversions to massive urban revitalization efforts.

A. Industrial to Residential Conversions (Loft Apartments)

Former factories, textile mills, and warehouses (often called brownfields) offer ideal shells for residential conversion.

Savings Driver: High ceilings, large floor plates, and expansive window openings, which would be prohibitively expensive to build today, are readily available. The “industrial aesthetic” is a major selling point, allowing developers to command premium rents while minimizing the cost of luxury finishes.

Example: The conversion of old industrial complexes in metropolitan areas like New York, London, and Berlin has consistently demonstrated that the retention of the concrete or heavy-timber frame offers a significantly lower cost per square foot for the structural buildout compared to constructing a similar unit in a newly built steel/concrete tower.

B. Office to Hotel or Residential Conversions

As the commercial office market evolves, converting obsolete office towers into hotels or apartments is becoming more common.

Savings Driver: The main structure and the expensive curtain wall (glass façade) are retained. The majority of the work is focused on the vertical distribution of utilities (plumbing risers) and the subdivision of the floor plate, which is less expensive than constructing the entire shell.

Cost Management: While plumbing can be complex, retaining the elevators, main stairwells, and primary fire suppression system provides significant capital savings that offset the complexity of converting the floor layout.

C. Governmental/Institutional to Community Centers

The repurposing of obsolete public buildings, like libraries, post offices, or schools, into mixed-use community centers or retail hubs.

Savings Driver: These buildings often feature high-quality, durable materials (granite, marble, long-lasting brick) and robust structural systems. Developers save on the material procurement cost of these expensive, high-quality finishes.

Community Support: The public benefit of preserving a cherished local landmark often eases the path through local government approvals, translating to the aforementioned time and cost savings.

Risk Management and Insurance Considerations

For insurance companies and risk assessors, adaptive reuse presents a unique set of variables. Understanding these is key to securing favorable coverage.

A. Builder’s Risk and Unique Exposure

During the construction phase, the project requires builder’s risk insurance. Adaptive reuse projects have slightly different risk exposures than new construction.

Increased Property Valuation: The existing structure holds a definite value that must be accounted for in the insurance policy’s total insured value (TIV), which differs from new construction where the value accrues over time.

Hazard Abatement Risk: The process of removing hazardous materials (asbestos, lead) is a specialized, high-risk activity that requires specific insurance riders to cover potential environmental liability and worker injury.

B. Professional Liability for Specialized Consultants

Adaptive reuse is inherently more complex from an engineering and architectural standpoint than a standardized new build. This increases the exposure for Professional Liability Insurance (Errors and Omissions, or E&O).

Non-Standard Engineering: Engineers must work with existing unknown conditions, which carries greater risk than designing a structure from scratch. They are essentially reverse-engineering and integrating new systems into an old framework.

Thorough Documentation: Insurers look favorably upon projects where the initial PCA and structural assessments are meticulously documented and peer-reviewed, as this demonstrates a proactive approach to risk identification and mitigation.

Conclusion: The Future of Profitable Development

The evidence overwhelmingly supports adaptive reuse as a superior financial model for modern development. It is not a secondary choice when new construction is unfeasible; it is a primary, strategic choice for achieving lower renovation costs, accelerated schedules, and superior market differentiation. By retaining the existing structural mass, developers dramatically cut expenses associated with demolition, foundation work, and structural framing. The added benefits of accessing historic tax credits, achieving faster permitting, and capitalizing on the unique character of repurposed space solidify its economic viability.

For investors, the mantra is clear: Look up, not just down. The most profitable next project may not be a new foundation poured on a vacant lot, but a forgotten, architecturally rich structure awaiting a smart, cost-conscious transformation. Adaptive reuse is the strategic intersection of preservation, profitability, and progress, making it the definitive path forward for sensible and sustainable real estate development. The combination of reduced hard costs, strategic tax incentives, and expedited time-to-market positions adaptive reuse as the smart, cost-saving, and highly profitable answer to urban revitalization.