The rapid growth of global cities has created an urgent need for innovative architectural strategies that balance human density with ecological preservation. As millions of people migrate toward metropolitan hubs every month, the pressure on housing, transportation, and energy systems has reached a critical breaking point. We can no longer rely on traditional urban sprawl models that consume vast amounts of land and resources without regard for long-term environmental consequences. Modern urbanization requires a fundamental shift toward vertical integration, circular economy principles, and green infrastructure that breathes life back into concrete jungles.

Architects and urban planners are now tasked with creating “living” cities that manage their own waste, generate renewable power, and provide high-quality communal spaces for diverse populations. This movement is not just about aesthetics; it is a survival strategy aimed at mitigating the effects of climate change while enhancing the mental well-being of city dwellers. By utilizing smart technology and biophilic design, we can transform stagnant urban centers into vibrant, self-sustaining ecosystems. This article explores the cutting-edge solutions that are defining the next era of urban development and how they can be implemented on a global scale.

The Rise of Vertical Forest Architecture

One of the most striking solutions to modern urbanization is the integration of massive amounts of vegetation directly into high-rise buildings. Vertical forests act as living filters that absorb carbon dioxide, filter fine dust particles, and release oxygen into the immediate surroundings.

Beyond their air-purifying capabilities, these structures provide natural insulation, reducing the energy needed for cooling during hot summer months. They also contribute to urban biodiversity by providing habitats for birds and insects that are typically displaced by traditional construction.

A. Integrated Irrigation and Greywater Recycling

Vertical forests use sophisticated plumbing systems to distribute recycled water to thousands of trees and shrubs. This minimizes water waste while keeping the building’s exterior vibrant and healthy throughout the year.

B. Wind Resistance and Structural Support

Engineers must design specialized balconies that can withstand the weight of soil and the force of wind acting on large trees. This requires a deep understanding of load-bearing materials and aerodynamic physics.

C. Biodiversity and Habitat Creation

By selecting native plant species, architects can create miniature ecosystems that support local wildlife. This helps bridge the gap between human environments and the natural world.

D. Natural Humidity and Temperature Control

The transpiration process of plants naturally cools the air around the building. This effect helps combat the “urban heat island” phenomenon that plagues modern metropolitan areas.

E. Psychological Benefits for Residents

Living in close proximity to nature has been proven to lower stress levels and improve cognitive function. Vertical forests bring the peace of the woods into the heart of the city.

F. Acoustic Insulation from City Noise

Thick layers of foliage act as a natural sound barrier against traffic and industrial noise. This creates a much quieter and more serene indoor environment for inhabitants.

G. Carbon Sequestration at Scale

Every square meter of a vertical forest contributes to the reduction of a city’s carbon footprint. Over time, these buildings act as massive air cleaners for the entire neighborhood.

H. Maintenance and Robotic Gardening

Modern vertical forests often use automated sensors and drones to monitor the health of the plants. This ensures that the greenery remains lush without requiring dangerous manual labor at high altitudes.

Smart Mobility and Transit-Oriented Development

Sustainable urbanization is impossible without a radical rethinking of how people move within a city. Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) focuses on creating high-density, mixed-use communities centered around high-quality public transport hubs.

By reducing the reliance on private vehicles, cities can reclaim massive amounts of land currently used for parking lots and wide highways. This land can then be repurposed for parks, pedestrian walkways, and affordable housing units.

A. The 15-Minute City Concept

The goal is to design neighborhoods where every daily necessity is within a 15-minute walk or bike ride. This drastically reduces the need for long-distance commuting and lowers carbon emissions.

B. Micro-Mobility Integration

E-scooters, bicycles, and autonomous shuttles act as “last-mile” solutions that connect residents to larger transit networks. These systems must be supported by dedicated, safe infrastructure.

C. High-Speed Rail Connectivity

Linking satellite cities with high-speed rail allows for regional economic growth without increasing road traffic. It provides a fast, sustainable alternative to short-haul flights.

D. Pedestrian-First Urban Zoning

Prioritizing walkways and car-free zones encourages physical activity and social interaction. It makes the city streets safer for children and the elderly alike.

E. Smart Traffic Management Systems

AI-driven traffic lights and sensors can optimize the flow of public transport in real-time. This reduces idling time and ensures that buses and trams are always the fastest way to travel.

F. Subterranean Logistics and Delivery

Moving freight and package delivery underground frees up the surface for human use. Automated tunnels can transport goods silently and efficiently across the city.

G. Multi-Modal Transit Hubs

Modern stations should serve as community centers that include libraries, shops, and healthcare facilities. This turns a transit stop into a destination in its own right.

H. Electric Vehicle (EV) Charging Infrastructure

As private cars are phased out, the remaining vehicles must be electric. Charging stations should be integrated into the existing grid using renewable energy sources.

Circular Economy and Waste-to-Energy Systems

A sustainable city must operate like a closed loop, where waste is viewed as a resource rather than a burden. Circular urbanism involves designing buildings and systems that facilitate easy recycling and material reuse.

Waste-to-energy plants are being integrated directly into urban neighborhoods, providing heat and electricity from non-recyclable materials. These facilities are often designed with public amenities, such as rooftop ski slopes or parks, to make them part of the community.

A. Modular Construction for Deconstruction

Buildings should be designed like LEGO sets, allowing components to be taken apart and reused in new projects. This significantly reduces the amount of demolition waste sent to landfills.

B. On-Site Organic Waste Composting

Neighborhood-scale composting systems turn food waste into nutrient-rich soil for urban farms. This eliminates the carbon cost of transporting heavy organic waste over long distances.

C. Greywater and Blackwater Treatment

Advanced filtration systems allow buildings to treat their own wastewater for use in toilets and cooling systems. This reduces the strain on municipal water supplies and prevents pollution.

D. Plastic-to-Brick Transformation

Innovations in material science allow non-recyclable plastics to be compressed into durable building blocks. This provides a low-cost, sustainable alternative to traditional concrete.

E. Renewable Energy Microgrids

Solar panels and small wind turbines on every roof create a decentralized power network. Excess energy can be shared between buildings, increasing the overall resilience of the city.

F. District Heating and Cooling

Using the excess heat from industrial processes to warm nearby homes is a highly efficient strategy. It eliminates the need for individual boilers and reduces total energy consumption.

G. Urban Mining and Material Banks

Cities are beginning to track the materials stored within their buildings as a “bank” for future use. This ensures that valuable metals and minerals are never truly lost.

H. Automated Vacuum Waste Collection

Underground pipes can suck trash directly from buildings to processing centers. This removes garbage trucks from the streets, reducing noise, traffic, and odors.

Biophilic Design and Mental Health

Biophilic design is the practice of connecting people with nature within the built environment. It goes beyond just adding plants; it involves using natural light, organic shapes, and natural materials to create a soothing atmosphere.

In densely populated cities, the lack of nature can lead to high rates of anxiety and depression. By integrating water features and natural ventilation, architects can create sanctuaries that rejuvenate the human spirit.

A. Daylighting and Solar Access

Strategic building orientation and the use of light wells ensure that every room receives natural sunlight. This regulates the human circadian rhythm and reduces the need for artificial lighting.

B. Organic Shapes and Fractal Patterns

Human brains are wired to find comfort in the repeating patterns found in nature. Using curved walls and natural textures makes buildings feel more welcoming and less institutional.

C. Natural Ventilation and Airflow

Designing buildings that breathe naturally reduces the reliance on mechanical HVAC systems. It provides residents with fresh air and a physical connection to the outdoor climate.

D. Indoor Water Features and Biophony

The sound of running water can mask city noise and create a sense of tranquility. It also helps humidify the air and cool the indoor environment naturally.

E. Living Walls and Rooftop Gardens

Internal green walls act as natural air filters and visual focal points. Rooftop gardens provide residents with space for social gathering and personal relaxation.

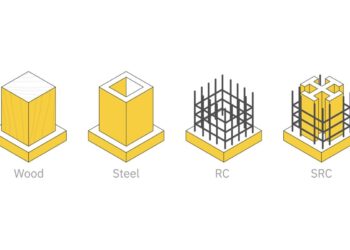

F. Use of Natural Timber and Stone

Natural materials have a lower carbon footprint than steel and concrete. They also age beautifully and provide a tactile connection to the Earth.

G. Views of Greenery from Every Window

Zoning laws should ensure that all residents have a “right to a view” of nature. Even a small park or a few trees can significantly impact a person’s mood.

H. Scent and Air Quality Management

Using aromatic plants and high-quality filtration ensures that the indoor air smells fresh and clean. This creates a sensory experience that is far superior to stale, recirculated air.

The Role of Urban Farming and Food Security

As cities grow, they become increasingly dependent on distant rural areas for food. This creates a vulnerable supply chain and high transportation emissions. Urban farming solutions bring food production into the heart of the city.

Vertical farms and rooftop greenhouses can produce massive amounts of leafy greens and vegetables using 90% less water than traditional farming. These facilities can be located in abandoned warehouses or integrated into new residential developments.

A. Hydroponic and Aeroponic Systems

These soil-less growing methods allow plants to grow faster and in much smaller spaces. They are ideal for the controlled environments of urban vertical farms.

B. Community Allotment Gardens

Providing space for residents to grow their own food fosters a sense of community and self-reliance. It also educates younger generations about where their food comes from.

C. Edible Landscaping in Public Parks

Instead of ornamental grass, cities can plant fruit trees and berry bushes. This provides free, healthy snacks for citizens and increases the city’s overall food resilience.

D. Aqua-Phonics: Fish and Plant Symbiosis

These systems combine fish farming with vegetable production. The waste from the fish provides nutrients for the plants, which in turn clean the water for the fish.

E. Automated Rooftop Greenhouses

Using the excess heat from a building to warm a greenhouse allows for year-round food production. This turns an unused roof into a productive asset.

F. Shortening the Farm-to-Table Loop

Selling urban-grown produce in local markets eliminates the need for plastic packaging and long-haul shipping. It ensures that the food is as fresh and nutrient-dense as possible.

G. Pollinator-Friendly Urban Planning

Cities must include “bee corridors” to ensure that urban farms are properly pollinated. This involves planting specific wildflowers across the city to support declining bee populations.

H. Food Waste Upcycling for Animal Feed

Excess food that cannot be composted can be processed into high-quality feed for local poultry or fish farms. This further closes the circular loop of the city’s food system.

Advanced Materials for Carbon-Negative Building

The construction industry is one of the largest contributors to global carbon emissions. To reach true sustainability, we must move beyond traditional concrete and steel toward materials that actually store carbon.

Mass timber, hempcrete, and carbon-absorbing concrete are changing the way we build. These materials are not only more sustainable but often provide better insulation and fire resistance than their traditional counterparts.

A. Mass Timber and Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT)

Timber acts as a carbon sink, locking away CO2 for the life of the building. CLT panels are as strong as steel and allow for faster, quieter construction.

B. Hempcrete for Natural Insulation

Hempcrete is a mixture of hemp shives and lime that is carbon-negative and highly breathable. It provides excellent thermal mass, keeping buildings warm in winter and cool in summer.

C. Carbon-Capture Concrete

Some new concrete formulas inject CO2 directly into the mix during the curing process. This makes the concrete stronger while permanently removing carbon from the atmosphere.

D. Self-Healing Bio-Concrete

Bacteria embedded in the concrete can “heal” cracks by producing limestone when exposed to water. This drastically increases the lifespan of infrastructure and reduces repair costs.

E. Recycled Steel and Aluminum

Using recycled metals requires a fraction of the energy needed to produce new materials. Architects are increasingly sourcing steel from demolished buildings for new projects.

F. Bio-Plastics and Mycelium Insulation

Mushroom-based materials (mycelium) can be grown into specific shapes to provide fire-resistant, biodegradable insulation. This is a radical alternative to petroleum-based foams.

G. Translucent Wood and Solar Glass

New materials allow windows to generate electricity while providing insulation. This turns the entire “skin” of a building into a giant solar panel.

H. 3D-Printed Earth and Clay Homes

Using local soil for 3D printing eliminates the need to transport heavy building materials. It allows for highly customized, low-cost housing that is perfectly adapted to the local climate.

Resilient Infrastructure for Climate Adaptation

Modern urbanization must account for the increasing frequency of extreme weather events. Resilient infrastructure is designed to absorb the impact of floods, storms, and heatwaves without catastrophic failure.

The “Sponge City” concept is a prime example of this, where urban surfaces are designed to absorb and store rainwater rather than letting it flood the streets. This water can then be filtered and reused during periods of drought.

A. Permeable Pavement and Green Streets

Replacing asphalt with porous materials allows rainwater to soak into the ground. This recharges local aquifers and prevents overwhelming the sewer system during storms.

B. Integrated Flood Barriers and Parks

Waterfront parks can be designed to act as floodplains during high-water events. When the water recedes, the area returns to its function as a public recreational space.

C. Heat-Reflective Cool Roofs

Painting roofs with white, reflective coatings can lower indoor temperatures by several degrees. This simple solution reduces the energy demand for air conditioning across the entire city.

D. Decentralized Water Storage Tanks

Installing large storage tanks under plazas and buildings provides a buffer during heavy rain. This stored water is a vital resource for firefighting and irrigation.

E. Wind-Resistant Building Envelopes

As storms become more intense, buildings must be designed with aerodynamic shapes to reduce wind load. This prevents structural damage and ensures the safety of residents.

F. Solar-Powered Emergency Grids

In the event of a total power failure, microgrids can provide essential electricity to hospitals and shelters. This ensures that the city’s critical functions remain active.

G. Coastal Mangrove Restoration

For coastal cities, restoring natural mangroves is much more effective than building concrete sea walls. Mangroves absorb wave energy and provide a natural defense against erosion.

H. Modular Floating Architecture

In areas threatened by rising sea levels, floating neighborhoods provide a flexible solution. These communities can rise and fall with the tide, ensuring they are never flooded.

Inclusive Design and Social Sustainability

A truly sustainable city is one that works for everyone, regardless of their age, income, or physical ability. Social sustainability involves creating spaces that promote equity and prevent the displacement of marginalized communities.

This requires a focus on affordable housing, accessible public services, and “universal design” principles. When people feel a sense of ownership and belonging in their city, they are more likely to take care of it.

A. Universal Design for All Ages

Buildings and streets should be navigable for everyone, including those with strollers or wheelchairs. This removes physical barriers to participation in urban life.

B. Mixed-Income Housing Developments

Integrating affordable housing into luxury developments prevents the creation of “wealth ghettos.” It ensures that essential workers can afford to live close to their jobs.

C. Public Spaces for Social Cohesion

Plazas, libraries, and community centers act as the “living rooms” of the city. These spaces are essential for building trust and understanding between different social groups.

D. Participatory Urban Planning

Residents should have a direct say in how their neighborhoods are developed. This ensures that new projects meet the actual needs of the people living there.

E. Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage

Transforming old factories or churches into community hubs preserves a city’s history while meeting modern needs. It gives a sense of continuity and identity to the urban fabric.

F. Safety Through Active Streetscapes

Designing streets with “eyes on the road” through ground-floor shops and cafes makes neighborhoods safer. Active streets discourage crime and foster a sense of security.

G. Equitable Access to Green Space

Parks should be distributed evenly across the city, not just in wealthy areas. Every citizen deserves a place to rest and exercise in a clean, natural environment.

H. Digital Inclusion and Smart Services

Providing free public Wi-Fi and digital literacy programs ensures that no one is left behind in the smart city revolution. Access to information is a fundamental right in the modern age.

Conclusion

Designing sustainable solutions is the only way to ensure the long-term success of modern urbanization. Architects must prioritize the integration of nature into the built environment to improve air quality. Transit-oriented development is essential for reducing our global reliance on fossil fuels and cars. The transition to a circular economy will transform how we manage urban waste and resources. Biophilic design principles are key to protecting the mental health of future city residents. Urban farming will play a vital role in securing a reliable food supply for growing populations.

Innovation in building materials is necessary to turn the construction industry carbon-negative. Resilient infrastructure will allow our cities to withstand the increasing threats of climate change. Social sustainability ensures that urban growth benefits all members of society equally. Smart technology must be used as a tool to enhance human life rather than just monitor it. Collaborative planning between citizens and experts leads to more vibrant and livable neighborhoods. The cities of the future will be defined by their ability to harmonize with the natural world. We have the tools and the knowledge to create a better urban future for everyone on Earth.