Introduction: A New Dawn for Building

The world is at a crossroads. As climate change accelerates and resources dwindle, the way we build and inhabit our spaces must fundamentally shift. For decades, the construction industry has been a major contributor to environmental degradation, responsible for a significant portion of global carbon emissions and waste. But a quiet revolution is underway—one that prioritizes not just aesthetics and function, but the very long-term health of our planet. This is the era of sustainable building, a comprehensive approach that future-proofs our structures against environmental challenges and creates healthier, more resilient communities. It’s more than a trend; it’s a necessity, an unseen force that is rapidly reshaping our built world from the ground up.

Sustainable design is not a single, isolated technique but a holistic philosophy. It encompasses everything from the materials we choose to the energy systems we integrate, and the very lifespan of a building. The ultimate goal is to minimize a structure’s environmental footprint throughout its entire lifecycle—from design and construction to operation, maintenance, and eventual demolition. This forward-thinking perspective is moving away from the “take-make-dispose” model and embracing a circular economy where resources are used efficiently and endlessly.

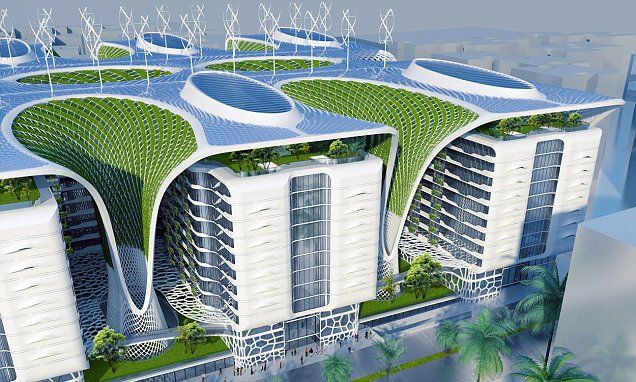

The principles of sustainable design are as varied as they are crucial. They involve a deep understanding of site selection, the use of renewable resources, and the creation of systems that are both energy and water-efficient. This revolution is powered by innovation and a growing awareness that the cost of inaction far outweighs the investment in sustainable solutions. From the towering skyscrapers in urban centers to the humble single-family home, every structure is a potential canvas for a more sustainable future.

Key Pillars of Sustainable Architecture

To truly understand sustainable building, we must break it down into its core components. These pillars are interconnected and, when applied together, create a symbiotic system that benefits both the occupants and the environment.

A. Passive Design: Working with Nature, Not Against It

The most fundamental aspect of sustainable building often involves the simplest solutions. Passive design is about using a building’s orientation, materials, and form to naturally regulate its temperature and lighting. It’s a return to time-honored architectural wisdom, enhanced by modern technology. A building’s placement on the site is critical. By orienting a structure to take advantage of natural sunlight in the winter and provide shade in the summer, we can dramatically reduce the need for artificial heating and cooling. This includes considerations like large south-facing windows in the Northern Hemisphere to capture solar gain, and deep overhangs or brise-soleil to block high summer sun.

Materials play a crucial role as well. High thermal mass materials, like concrete or brick, can absorb and store heat during the day and release it at night, helping to stabilize indoor temperatures. Conversely, proper insulation, made from recycled or natural materials like cellulose or sheep’s wool, is essential for preventing heat loss. The use of natural ventilation is another cornerstone. Strategically placed windows and openings can create a cross-breeze, eliminating the need for air conditioning during milder months. This not only saves energy but also improves indoor air quality. Passive design is the first, and most important, step toward a truly sustainable building, as it reduces energy demand before any active systems are even considered.

B. Material Selection: From Cradle to Grave

The choice of materials is one of the most impactful decisions in a building project. The focus of sustainable material selection is on their entire life cycle, from extraction and manufacturing to transportation, use, and eventual disposal. This is often referred to as a “cradle-to-grave” or, more ideally, a “cradle-to-cradle” approach. The goal is to use materials that are renewable, locally sourced, and have low embodied energy—the total energy consumed to produce and transport a material.

Consider the difference between traditional steel and recycled steel. The production of new steel is an energy-intensive process that generates significant carbon emissions. Recycled steel, on the other hand, requires a fraction of the energy and diverts waste from landfills. The same logic applies to wood from sustainably managed forests, bamboo, and reclaimed materials like salvaged timber or brick. These choices not only reduce the environmental footprint but can also lend unique character to a building. The growing popularity of materials like recycled glass countertops, cork flooring, and low-VOC (volatile organic compound) paints highlights a move towards healthier indoor environments as well.

C. Energy Efficiency and Renewable Systems

After passive design has minimized a building’s energy needs, the next step is to make the active systems as efficient as possible and to power them with renewable energy. This is where technologies like high-efficiency HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) systems, LED lighting, and smart thermostats come into play. These innovations allow a building to consume less energy while providing a more comfortable and responsive environment for its occupants.

The integration of on-site renewable energy sources, primarily solar panels, has become a cornerstone of modern sustainable design. The falling cost of photovoltaic technology has made it a viable option for a wide range of buildings, from residential homes to large commercial complexes. Solar panels can offset a significant portion, or even all, of a building’s electricity needs, transforming it from a consumer of energy into a producer. Other renewable energy sources, such as geothermal heat pumps, which use the earth’s stable temperature to heat and cool a building, are also gaining traction for their incredible efficiency.

D. Water Conservation: A Precious Resource

Water is a finite resource, and its conservation is a critical component of sustainable building. A building’s water system should be designed to minimize waste and maximize efficiency. This can be achieved through several strategies. High-efficiency fixtures, such as low-flow toilets, faucets, and showerheads, can significantly reduce water consumption without compromising performance.

Beyond fixture selection, more advanced systems like greywater recycling are becoming more common. Greywater, which is wastewater from sinks, showers, and laundry, can be treated and reused for non-potable purposes like toilet flushing and irrigation. Similarly, rainwater harvesting systems capture and store rainwater from a building’s roof, providing a free and sustainable source of water for landscaping and other uses. These systems not only conserve a precious resource but also reduce a building’s impact on local water infrastructure.

E. Lifecycle Assessment and Circular Economy

A truly sustainable building is one that considers its entire life, from inception to deconstruction. The concept of a “circular economy” is at the heart of this. Unlike a linear model where materials are used and discarded, a circular approach aims to keep materials in use for as long as possible. This is done by designing buildings for durability and adaptability, and by selecting materials that can be easily deconstructed and reused or recycled at the end of their life.

This is where the concept of a “Deconstructable Building” comes in. Instead of being demolished with heavy machinery, these buildings are designed so their components—from steel beams to window frames—can be carefully taken apart and reassembled elsewhere. This approach minimizes waste and preserves the value of materials. The focus on durability also means less need for maintenance and replacement, further reducing the environmental footprint over time. A lifecycle assessment (LCA) is a powerful tool used by architects to evaluate the environmental impact of a building at every stage of its life, helping them make informed decisions that reduce energy, water, and material use.

The Rise of Smart and Resilient Buildings

The future of sustainable building is deeply intertwined with technology. Smart building technology is a growing field that uses sensors, automation, and data analytics to optimize a building’s performance. For example, a smart thermostat can learn a building’s occupancy patterns and adjust heating and cooling accordingly. Smart lighting systems can turn off lights in unoccupied rooms, and automated blinds can respond to sunlight to prevent overheating. These systems not only save energy but also create a more responsive and comfortable environment for occupants.

Beyond efficiency, sustainable design is also increasingly focused on resilience. As climate change leads to more extreme weather events, buildings must be designed to withstand floods, hurricanes, and wildfires. This involves using durable, fire-resistant materials, elevating buildings in flood zones, and incorporating features like green roofs to manage stormwater runoff. These designs are not just about environmental protection but also about human safety and long-term economic stability. A resilient building is a sustainable building, and vice versa.

The Business Case for Sustainable Building

While the environmental benefits are clear, there is also a compelling financial argument for sustainable design. The initial cost of building sustainably can sometimes be higher, but these costs are often recouped quickly through significant savings on energy and water bills. A building with a lower operational cost has a higher market value, making it a more attractive asset for investors and occupants alike.

Furthermore, many governments and municipalities now offer incentives, tax breaks, and faster permitting for green buildings. This recognition of sustainable design as a public good is a powerful driver for change. Companies are also finding that buildings designed for health and well-being lead to higher employee productivity and retention. The use of natural light, good air quality, and access to outdoor spaces can have a measurable positive impact on a workforce. A sustainable building is not just an environmental investment; it’s a smart business decision.

Conclusion

The shift towards sustainable building is not a temporary fad but a fundamental recalibration of our relationship with the built environment. It is a response to an urgent global need, driven by innovative design, smart technology, and a growing understanding of the economic benefits. By focusing on passive design, sustainable materials, energy efficiency, water conservation, and lifecycle thinking, we are not just building structures; we are building a more resilient, equitable, and habitable future for generations to come.

This revolution is an unseen force, working quietly to transform a once-destructive industry into a powerful engine for positive change. Every decision, from the choice of a single nail to the orientation of an entire building, holds the potential to reduce our footprint and create spaces that thrive in harmony with the natural world. The future of architecture isn’t about grand gestures; it’s about thoughtful, responsible design that stands the test of time.